|

Understanding Capitalism Part II: Personal Property,

Money and Finance

By  -

November 21, 2004 -

November 21, 2004

There are several major thinkers which are recognized as important in

laying the foundation for the development of modern representative

government and capitalist economy. Adam Smith is one such man and John

Locke is another.

John Locke is a 17th century empiricist philosopher who had a

profound impact on the Enlightenment and the development of political

philosophy. Like Adam Smith, Locke is often misunderstood today. Because

Locke's ideas were fundamental in the development of representative

government, the separation of Church and State, personal property and

free enterprise, many people today improperly look to John Locke as an

ideological supporter of present day American capitalism.

Locke, who lived before the development of capitalism, is famous for

being a champion of "liberty" and promoting a system of checks and

balances within a limited government, as well as arguing for the

importance of a natural right to personal property.

What exactly is personal property then, and in what way did John

Locke defend it? How does our modern economic system affect our views of

personal property? How does the evolving nature of money affect our

understanding of value?

To understand the development of the modern concept of personal

property and its association with "liberty" one must first understand

the climate out of which these concepts arose.

In the 1600s, when John Locke lived, Europe was still ruled by

theocratic monarchs, who claimed that their power to rule, and their

right to ownership of all property, came from God. During this time it

was established that all property was effectively owned by the King and

Queen. The King and/or Queen then disseminated control over this

property throughout the kingdom, typically by matter of family lineage

and loyalty to the King.

It is from this position that Locke begins his argument for man's

natural right to "personal property" - an argument against the right of

royalty to hold ownership of value that individuals create with their

own labor.

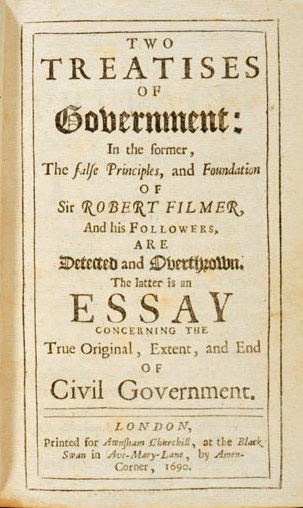

In 1690 Locke finished what is now considered to be one of his

masterpieces, Second Treatise on Civil Government.

In this work Locke directly addresses the issue of personal property:

Whether we consider natural reason, which tells us that men, being

once born, have a right to their preservation, and consequently to

meat and drink and such other things as Nature affords for their

subsistence, or "revelation," which gives us an account of those

grants God made of the world to Adam, and to Noah and his sons, it

is very clear that God, as King David says (Psalm 115. 16), "has

given the earth to the children of men," given it to mankind in

common. But, this being supposed, it seems to some a very great

difficulty how any one should ever come to have a property in

anything. I will not content myself to answer, that, if it be

difficult to make out "property" upon a supposition that God gave

the world to Adam and his posterity in common, it is impossible that

any man but one universal monarch should have any "property" upon a

supposition that God gave the world to Adam and his heirs in

succession, exclusive of all the rest of his posterity; but I shall

endeavour to show how men might come to have a property in several

parts of that which God gave to mankind in common, and that without

any express compact of all the commoners.

Here Locke has laid out his starting position. Locke then goes on to

further clarify the natural condition of the property of the earth:

God, who hath given the world to men in common, hath also given

them reason to make use of it to the best advantage of life and

convenience. The earth and all that is therein is given to men for

the support and comfort of their being. And though all the fruits it

naturally produces, and beasts it feeds, belong to mankind in

common, as they are produced by the spontaneous hand of Nature, and

nobody has originally a private dominion exclusive of the rest of

mankind in any of them, as they are thus in their natural state, yet

being given for the use of men, there must of necessity be a means

to appropriate them some way or other before they can be of any use,

or at all beneficial, to any particular men. The fruit or venison

which nourishes the wild Indian, who knows no enclosure, and is

still a tenant in common, must be his, and so his- i.e., a part of

him, that another can no longer have any right to it before it can

do him any good for the support of his life.

Locke has made the claim that all things in their natural state are

common, i.e. public, resources, but he then goes on to establish the

basis by which these common resources can be said to become personal

property in what is now one of his famous statements. What I have marked

in bold is a quote that is often taken out of context:

Though the earth and all inferior creatures be common to all men,

yet every man has a "property" in his own

"person." This nobody has any right to but himself. The "labour" of

his body and the "work" of his hands, we may say, are properly his.

Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the state that Nature hath

provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with it, and

joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his

property. It being by him removed from the common state Nature

placed it in, it hath by this labour something annexed to it that

excludes the common right of other men. For this "labour" being the

unquestionable property of the labourer, no man but he can have a

right to what that is once joined to, at least where there is

enough, and as good left in common for others.

He that is nourished by the acorns he picked up under an oak, or

the apples he gathered from the trees in the wood, has certainly

appropriated them to himself. Nobody can deny but the nourishment is

his. I ask, then, when did they begin to be his? when he digested?

or when he ate? or when he boiled? or when he brought them home? or

when he picked them up? And it is plain, if the first gathering made

them not his, nothing else could. That labour put a distinction

between them and common. That added something to them more than

Nature, the common mother of all, had done, and so they became his

private right. And will any one say he had no right to those acorns

or apples he thus appropriated because he had not the consent of all

mankind to make them his? Was it a robbery thus to assume to himself

what belonged to all in common? If such a consent as that was

necessary, man had starved, notwithstanding the plenty God had given

him. We see in commons, which remain so by compact, that it is the

taking any part of what is common, and removing it out of the state

Nature leaves it in, which begins the property, without which the

common is of no use...

By making an explicit consent of every commoner necessary to any

one's appropriating to himself any part of what is given in common.

Children or servants could not cut the meat which their father or

master had provided for them in common without assigning to every

one his peculiar part. Though the water running in the fountain be

every one's, yet who can doubt but that in the pitcher is his only

who drew it out? His labour hath taken it out of the hands of Nature

where it was common, and belonged equally to all her children, and

hath thereby appropriated it to himself.

Thus this law of reason makes the deer that Indian's who hath

killed it; it is allowed to be his goods who hath bestowed his

labour upon it, though, before, it was the common right of every

one. And amongst those who are counted the civilised part of

mankind, who have made and multiplied positive laws to determine

property, this original law of Nature for the beginning of property,

in what was before common, still takes place, and by virtue thereof,

what fish any one catches in the ocean, that great and still

remaining common of mankind; or what amber-gris any one takes up

here is by the labour that removes it out of that common state

Nature left it in, made his property who takes that pains about it.

And even amongst us, the hare that any one is hunting is thought his

who pursues her during the chase. For being a beast that is still

looked upon as common, and no man's private possession, whoever has

employed so much labour about any of that kind as to find and pursue

her has thereby removed her from the state of Nature wherein she was

common, and hath begun a property.

Here Locke has provided the basis of what can be described as the

"Natural Law" definition of personal property. The Natural Law concept

of personal property is that an individual has a right to own value that

that individual has himself created through his own labor.

This concept of property is important to understand because it is

actually very different from the concept of property under the

capitalist system, which developed some 100 years after the time of

Locke.

Under the capitalist system the right to ownership of newly created

value comes from ownership of the tools used to create the new value,

not from the labor used to create the new value. This is the basis of

the capitalist concept of private ownership of the "means of

production". The owner of the means of production retains the ownership

rights to everything that is produced using that means of production. If

one is self-employed then one owns their own means of production, and

thus retains ownership to the fruits of their own labor. If one is

employed by another private entity, however, then one does not retain

any rights to ownership of the value produced by their labor under the

capitalist system, the capital owner does.

The distinction between the Natural Law form of ownership and

capitalist ownership can be demonstrated with an example.

Let us take for example the building of a log cabin as a means to

demonstrate the natural right described by Locke of an individual to the

product of his labor. If you were to go out into the woods with an axe

and chop down trees and cut and organize those trees in such a way as to

build a log cabin for yourself to live in then this is an example of how

Locke's definition of man's right to personal property is established.

In this case, you have, through your labor, created value, and you

have a right to ownership of this value that you have created.

Under the capitalist system, a wage laborer would be paid a wage that

would be determined by the labor market, instead of being compensated

with the product of his labor. Instead of working to create value,

capitalists can simply own property that is used to create value, and

then by paying a wage that is less than the value of the product of

labor to the workers, a capitalist can acquire property without working

himself. A capitalist retains the legal right to value that workers

create via laws that are enforced by the government.

When America was founded 95% of Americans were primary producers,

i.e. farmers, pioneers, lumberjacks, fishermen, etc. They were engaged

in the creation and acquisition of property in a manner similar to that

described by John Locke above, which is to say that property owned by

individuals was generally property that was in fact created by the labor

of those same individuals. The right to ownership of their property was

granted by the fact that they labored to create it. Wage labor did not

exist. In addition, early Americans were extremely skeptical of banks

and thus usury was very uncommon. This was for a variety of reasons,

including the fact that many early Americans were men fleeing debtor's

prisons in Europe, barter simply made more sense in a wild place like

early America, without central control mechanisms banks issuing paper

money quickly over printed and inflation made their notes worthless, the

use of purely gold and silver coins was problematic in a variety of ways

(control of metal purity, fluctuating value of metals, etc), many early

Americans were anti-Semitic and banking was seen an a Jewish activity,

many of the early American Christian groups opposed usury for religious

reasons, and most Americans were self-sufficient and simply didn't have

much need for high finance.

This is important to understand when understanding the early American

defense of personal property and the association between liberty and

personal property in early America. The concept of personal property

championed by early Americans was that of John Locke's - of a person's

right to own value that they create through their own labor. It is

unfortunate, however, that this right to value was only respected for

white males and did not extend to Natives, women, and obviously not to

slaves.

Though the majority of Americans were primary producers, there were

also merchants, such as the men of the Massachusetts Bay East India

Company. Some of these merchants did make very high profits from trade,

however, this mercantile activity did not constitute capitalism in that

it was not based on ownership of the means of production, but rather on

the trade of goods acquired from people who owned and controlled their

own productive means and labor.

It is important to remember that in fact capitalism as an economic

system did not exist in America, or anywhere in the world, when America

was founded. America's initial defense of private property was largely a

defense of Natural Law property rights as they saw them - protecting the

right to ownership of value created by white males, their families and

their slaves against the existing so-called divine right of aristocracy.

Locke went on to further discuss his concept of personal property:

It will, perhaps, be objected to this, that if gathering the acorns

or other fruits of the earth, etc., makes a right to them, then any

one may engross as much as he will. To which I answer, Not so. The

same law of Nature that does by this means give us property, does

also bound that property too. "God has given us all things

richly." Is the voice of reason confirmed by inspiration? But

how far has He given it us- "to enjoy"? As much as any one can make

use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much he may by

his labour fix a property in. Whatever is beyond this is more than

his share, and belongs to others. Nothing was made by God for man to

spoil or destroy. And thus considering the plenty of natural

provisions there was a long time in the world, and the few spenders,

and to how small a part of that provision the industry of one man

could extend itself and engross it to the prejudice of others,

especially keeping within the bounds set by reason of what might

serve for his use, there could be then little room for quarrels or

contentions about property so established.

Here Locke has argued that though someone can acquire a right to

ownership of property through the use of their own labor, that right

only extends so far as the individual does not acquire more than they

can use and insofar as their labor is not destructive. In other words,

Locke argues that his position that a person's labor grants them a right

to ownership of property does not mean that someone has the right to

accumulate more than they can use because all things are, in their

natural state, a part of the common resources available to all people

equally. By taking more than one could personally use, Locke argued that

such an act amounted to taking more than one's "fair share", and thus

deprived others of access to potentially needed resources without cause.

This view of ownership was present to some degree in colonial America,

but one of the defining features of American property rights after the

Revolution was the so-called "right to waste". In other words, America

pioneered the right of complete ownership by individuals with zero

social obligation. This was likely heavily influenced by the extreme

bounty that existed in America at the time.

Locke then provides what he considers to be the basis by which

ownership of land could be determined. Since land is not something that

people produce, and is something that is originally held in common, how

then can land be titled to the ownership of an individual?

But the chief matter of property being now not the fruits of the

earth and the beasts that subsist on it, but the earth itself, as

that which takes in and carries with it all the rest, I think it is

plain that property in that too is acquired as the former. As much

land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the

product of, so much is his property. He by his labour does, as it

were, enclose it from the common. Nor will it invalidate his right

to say everybody else has an equal title to it, and therefore he

cannot appropriate, he cannot enclose, without the consent of all

his fellow-commoners, all mankind. God, when He gave the world in

common to all mankind, commanded man also to labour, and the penury

of his condition required it of him. God and his reason commanded

him to subdue the earth- i.e., improve it for the benefit of life

and therein lay out something upon it that was his own, his labour.

He that, in obedience to this command of God, subdued, tilled, and

sowed any part of it, thereby annexed to it something that was his

property, which another had no title to, nor could without injury

take from him.

Nor was this appropriation of any parcel of land, by improving it,

any prejudice to any other man, since there was still enough and as

good left, and more than the yet unprovided could use. So that, in

effect, there was never the less left for others because of his

enclosure for himself. For he that leaves as much as another can

make use of does as good as take nothing at all. Nobody could think

himself injured by the drinking of another man, though he took a

good draught, who had a whole river of the same water left him to

quench his thirst. And the case of land and water, where there is

enough of both, is perfectly the same.

According to Locke, land ownership was to to be determined by use. A

right to ownership of land was to be granted to individuals who actively

made use of it. By making use of the land you established your right to

own it. By using Locke's Natural Law right to land ownership today, land

would be cheaper and available to more people, but there would also be

increased pressure to use land to keep ownership of it. America's "right

to waste" (to hold a deed to land without using it) was critical in

transforming land into one of the first major commodities that would be

bought and sold in investment markets in America.

Right to ownership of land based on use is also a growing matter of

debate in poor and developing countries, where most of the land is owned

by a small wealthy class, but goes unused while millions of people have

no place to live. There are currently estimated to be 1 billion

squatters world wide. Squatters are defined as people who are using land

that they do not own.

The same measure may be allowed still, without prejudice to

anybody, full as the world seems. For, supposing a man or family, in

the state they were at first, peopling of the world by the children

of Adam or Noah, let him plant in some inland vacant places of

America. We shall find that the possessions he could make himself,

upon the measures we have given, would not be very large, nor, even

to this day, prejudice the rest of mankind or give them reason to

complain or think themselves injured by this man's encroachment,

though the race of men have now spread themselves to all the corners

of the world, and do infinitely exceed the small number was at the

beginning. Nay, the extent of ground is of so little value without

labour that I have heard it affirmed that in Spain itself a man may

be permitted to plough, sow, and reap, without being disturbed, upon

land he has no other title to, but only his making use of it. But,

on the contrary, the inhabitants think themselves beholden to him

who, by his industry on neglected, and consequently waste land, has

increased the stock of corn, which they wanted. But be this as it

will, which I lay no stress on, this I dare boldly affirm, that the

same rule of propriety- viz., that every man should have as much as

he could make use of, would hold still in the world, without

straitening anybody, since there is land enough in the world to

suffice double the inhabitants, had not the invention of money, and

the tacit agreement of men to put a value on it, introduced (by

consent) larger possessions and a right to them; which, how it has

done, I shall by and by show more at large.

Here Locke makes an important statement. He states that the use of

money, to enlarge possessions beyond that which a man can use, causes

the availability of land to be limited. This of course is because

individuals can then own more land than they can make use of.

Locke restates the importance of labor and plainly states his view on

the degree to which labor contributes to value. This is the basis of the

Labor Theory of Value, later to be used by Adam Smith, David Ricardo,

and Karl Marx.

Nor is it so strange as, perhaps, before consideration, it may

appear, that the property of labour should be able to overbalance

the community of land, for it is labour indeed that puts the

difference of value on everything; and let any one consider what the

difference is between an acre of land planted with tobacco or sugar,

sown with wheat or barley, and an acre of the same land lying in

common without any husbandry upon it, and he will find that the

improvement of labour makes the far greater part of the value. I

think it will be but a very modest computation to say, that of the

products of the earth useful to the life of man, nine-tenths are the

effects of labour. Nay, if we will rightly estimate things as they

come to our use, and cast up the several expenses about them- what

in them is purely owing to Nature and what to labour- we shall find

that in most of them ninety-nine hundredths are wholly to be put on

the account of labour.

From this basic position Locke then goes on to discuss the

development of the role of money and trade in society, and how these

things impact the concept of property:

Now of those good things which Nature hath provided in common,

every one hath a right (as hath been said) to as much as he could

use; and had a property in all he could effect with his labour; all

that his industry could extend to, to alter from the state Nature

had put it in, was his. He that gathered a hundred bushels of acorns

or apples had thereby a property in them; they were his goods as

soon as gathered. He was only to look that he used them before they

spoiled, else he took more than his share, and robbed others. And,

indeed, it was a foolish thing, as well as dishonest, to hoard up

more than he could make use of. If he gave away a part to anybody

else, so that it perished not uselessly in his possession, these he

also made use of And if he also bartered away plums that would have

rotted in a week, for nuts that would last good for his eating a

whole year, he did no injury; he wasted not the common stock;

destroyed no part of the portion of goods that belonged to others,

so long as nothing perished uselessly in his hands. Again, if he

would give his nuts for a piece of metal, pleased with its colour,

or exchange his sheep for shells, or wool for a sparkling pebble or

a diamond, and keep those by him all his life, he invaded not the

right of others; he might heap up as much of these durable things as

he pleased; the exceeding of the bounds of his just property not

lying in the largeness of his possession, but the perishing of

anything uselessly in it.

And thus came in the use of money; some lasting thing that men

might keep without spoiling, and that, by mutual consent, men would

take in exchange for the truly useful but perishable supports of

life.

And as different degrees of industry were apt to give men

possessions in different proportions, so this invention of money

gave them the opportunity to continue and enlarge them. For

supposing an island, separate from all possible commerce with the

rest of the world, wherein there were but a hundred families, but

there were sheep, horses, and cows, with other useful animals,

wholesome fruits, and land enough for corn for a hundred thousand

times as many, but nothing in the island, either because of its

commonness or perishableness, fit to supply the place of money. What

reason could any one have there to enlarge his possessions beyond

the use of his family, and a plentiful supply to its consumption,

either in what their own industry produced, or they could barter for

like perishable, useful commodities with others? Where there is not

something both lasting and scarce, and so valuable to be hoarded up,

there men will not be apt to enlarge their possessions of land, were

it never so rich, never so free for them to take. For I ask, what

would a man value ten thousand or an hundred thousand acres of

excellent land, ready cultivated and well stocked, too, with cattle,

in the middle of the inland parts of America, where he had no hopes

of commerce with other parts of the world, to draw money to him by

the sale of the product? It would not be worth the enclosing, and we

should see him give up again to the wild common of Nature whatever

was more than would supply the conveniences of life, to be had there

for him and his family.

Thus, in the beginning, all the world was America, and more so than

that is now; for no such thing as money was anywhere known. Find out

something that hath the use and value of money amongst his

neighbours, you shall see the same man will begin presently to

enlarge his possessions.

In discussing of the role of money in society Locke used colonial

America as an example of a place where "true commerce" had not yet

developed. Where, for the most part, the concept of property existed in

its basic and "natural" form. Indeed, there was no universally accepted

currency in colonial America. Barter was more common than the use of any

currency, and tobacco leaves were often used as a form of money well

after the Revolutionary War.

Locke then proceeded to discuss the effect of money in more detail:

But, since gold and silver, being little useful to the life of man,

in proportion to food, raiment, and carriage, has its value only

from the consent of men- whereof labour yet makes in great part the

measure- it is plain that the consent of men have agreed to a

disproportionate and unequal possession of the earth- I mean out of

the bounds of society and compact; for in governments the laws

regulate it; they having, by consent, found out and agreed in a way

how a man may, rightfully and without injury, possess more than he

himself can make use of by receiving gold and silver, which may

continue long in a man's possession without decaying for the

overplus, and agreeing those metals should have a value.

Above Locke touched on the fact that governments are established in

order to maintain a means by which great disparities of wealth can be

obtained. Without governments great disparities of wealth are virtually

impossible.

And thus, I think, it is very easy to conceive, without any

difficulty, how labour could at first begin a title of property in

the common things of Nature, and how the spending it upon our uses

bounded it; so that there could then be no reason of quarrelling

about title, nor any doubt about the largeness of possession it

gave. Right and conveniency went together. For as a man had a right

to all he could employ his labour upon, so he had no temptation to

labour for more than he could make use of. This left no room for

controversy about the title, nor for encroachment on the right of

others. What portion a man carved to himself was easily seen; and it

was useless, as well as dishonest, to carve himself too much, or

take more than he needed.

This is the conclusion of Locke's assessment of personal property in

his 1690 work, Second Treaties on Government, and unfortunately

it leaves something to be desired. What is clear, however, is that Locke

viewed value and the right to personal property as a product of labor

and he viewed the accumulation of more property that one could "make use

of" as a form of theft from the common good. He described how

governments formed in order to facilitate the accumulation of more

wealth than could naturally be acquired by one's self. However, Locke

did make other comments on the issue of money. He also wrote:

Let us next see how it [money] comes to be of the same Nature with

Land, by yielding a certain yearly Income, which we call Use or

Interest. For Land produces naturally something new and profitable,

and of value to Mankind; but money is a barren Thing, and produces

nothing, but by Compact, transfers that Profit, that was the Reward

of one Man's Labour, into another Man's Pocket.

- Folio edition of Locke's Works, 1740, Vol. II [p. 19]

And now we begin to get somewhere.

Money itself is not wealth. Money itself has no significant value

(other than the value of the raw materials that it is made of). Money is

a means of representing and transferring value.

Here Locke is specifically discussing interest on money, and Locke

correctly makes clear that interest on money always represents a

transfer of value that is created by some worker's labor to a

moneylender.

Money can only represent some value that has actually been created.

Creating money by itself without it representing any value is one thing

that leads to inflation.

The Origin and Evolution of Money

In order to understand how money works, like most things, it is

helpful to understand its development.

Money developed independently in a variety of cultures in a variety

of different ways. Despite the fact that the first tendency when

thinking about how money would likely have originated is to think of

money as way to make trade easier, this is not historically accurate.

Money commonly developed for religious and State practices.

Livestock served as one of the earliest forms of currency, which

other forms of money evolved out of. Cattle were not merely a form of

wealth, but were actually a medium of economic exchange. In fact

"capital", "chattel" and "cattle" all have the same linguistic root.

Livestock were also important in religious ceremonies as sacrificial

animals in many cultures. This may be why some other early forms of

money that came after cattle had religious significance as well. Money

was often reserved for important ceremonial purposes, such as

contributing to priests or for dowry payments - it was not used in

everyday transactions.

Taxation and "banking" also played an important role in the

development of money. In Egypt for example, commodities such as grain

were stored in large State silos for safekeeping. Peasants would deposit

their grain into these silos and be given a receipt.

Taxes were often demanded in the form of grain. In many cases the

appropriate amount of receipts would be turned over to the tax

collectors instead of the actual grain itself. These receipts were

mostly reserved for the payment of taxes or to retrieve the grain, but

they became a medium of exchange among individuals as well, though

barter still remained the dominant means of exchange.

Money continued to evolve, and its role in societies all around the

world continued to change throughout history, becoming increasingly

important as economies became more complex.

Despite the variety of forms of money that have existed throughout

history, the important thing to understand about money is that money is

something that represents value. Money itself is not generally

valuable, though in the case of cattle and some other forms of money

there is arguably an intrinsic value in the object itself, the main

function of money is to represent some other

form of value. Historically money has typically represented some real

material object of value.

When the Egyptians deposited grain into a State "bank" and received a

receipt in return, the value of that receipt was that it entitled the

holder to a specified quantity of grain or some other commodity in the

storehouse.

This, ultimately, is still the same role that money serves today,

however today money is more abstract and represents not only material

goods, but also service potential and intellectual property.

Money as Representative of Value

The understanding that money itself is not valuable (with the

exception of collectable money and money made from precious metals,

etc), but rather that it merely represents value, is perhaps the most

important concept to grasp in order to understand economics.

Because of this, one of the best ways to understand economics is to

forget about money and look at the real underlying forms of value.

Economic activity is not a matter of "making money" it is a matter of

producing goods and services. The objective of work is to create some

tangible value, not to "make money". Making money is quite simple, you

use a printing press and you print it. This, of course, achieves

absolutely nothing though.

One of the major problems that we have as individuals in

understanding the economy today is the complete separation of money from

that which money represents.

Money has become so abstract today that it is difficult for people to

fully comprehend economic exchanges. This difficulty provides an

opportunity for capitalists to further manipulate and exploit workers

and the system. This is compounded by the fact that value is a somewhat

abstract concept in the first place.

This business of Money and Coinage is by some Men, and amongst them

some very Ingenious Persons, thought a great Mystery, and very hard

to be understood. Not that truly in it self it is so: But because

interessed People that treat of it, wrap up the Secret they make

advantage of in mystical, obscure, and unintelligible ways of

Talking; Which Men, from a preconceiv'd opinion of the difficulty of

the subject, taking for Sense, in a matter not easie to be

penetrated, but by the Men of Art, let pass for Current without

Examination. Whereas, would they look into those Discourses, enquire

what meaning their Words have, they would find, for the most part,

either their Positions to be false; their Deductions to be wrong; or

(which often happens) their words to have no distinct meaning at

all.

- John Locke -

Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest

and the Raising the Value of Money Part 5.

Without money in the picture, production and economic exchange are

much easier to understand.

For example, if a man goes out into the woods and he cuts down a tree

and he uses the wood from the tree to make a table, then it is quite

obvious to the man, and everyone else, what his labor has created. The

table is a product of the man's work on a natural resource. The two

major constituent parts of the value come from the growth of the tree

(which the man did not create) and the work done in turning the tree

into something more useful.

The man rightfully owns the table and all of the value that is

imparted to it. If the man goes into the woods and he cuts down many

trees and he builds a full set of furniture and a log cabin, then it is

quite obvious that all of this property is rightfully his.

This is basically how property was understood by tribal groups and by

John Locke, as described above. An important aspect of this view of

property is that it was quite simple and direct to determine what

someone earned because the product of their labor was obvious and

direct.

Now, let's say that after making a full set of furniture the man

decides to trade it for other goods, a rowboat made by another man for

example.

In this case, both parties know exactly what they have created. They

understand the effort put into creating these products.

Not only that, but the idea behind Adam Smith's "invisible hand"

free-trade was that by allowing people to engage in commerce freely

people would be able to exchange goods that they deemed to be of equal

value with each other so that they could more easily get what they

needed, and this would encourage people to work to produce goods that

were needed by society.

The premise behind Adam Smith's concept was that every exchange of

goods would be an exchange of equal values. In other words,

there would be no profit in trade.

This is important to understand. Adam Smith's concept of private

enterprise was developed prior to the existence of capitalism as we know

it, and certainly prior to the existence of modern corporations.

His idea was that in a town by a river a man would be encouraged to

make boats in accordance to the social need for boats, and a man would

be encouraged to make bread according to the demand for bread, and this

would encourage men to work to create these goods in amounts that were

needed by society and in amounts that could be exchanged for other goods

of equal value.

By the thinking of both Adam Smith and John Locke labor was the basis

of the economy, and trade was not a means to "create profits", but

rather a means to exchange goods that were created by labor in an equal

and non-profitable manner.

This means that "wealth" was to be obtained by creating more goods.

One's wealth was to be dependant upon how much wealth that person, as an

individual, created.

Today, however, there are many other ways that individuals

appropriate wealth, such as through futures markets, stock exchanges,

dividends, currency speculation, land speculation, inheritance,

litigation, interest, etc., just to name a few. All of the afore

mentioned methods for obtaining wealth are methods by which wealth is

merely transferred, not created.

All of these methods of transfer of wealth are facilitated by the use

of money, and in all of these cases, value is transferred from the

workers who have created it, to others who did not create it.

All money that is gained from things like dividends, or the sale of

stocks, or the sale of land, and so on, represents a redistribution of

wealth. All of that value is value that had to have been created by some

worker. Money does not create money. It is often said that investing is

the process of "putting your money to work for you". This is not really

what investing is, because money cannot work, money cannot create value,

only work (either done by man (machines being an extension of man) or

nature) can create value. Money does not work, people work. Investing is

buying rights to a share of the work that other people do.

All value that is obtained from "investing", etc., is value that had

to be created by someone else.

When someone "makes" millions of dollars in the stock market, or by

trading gold, etc., they aren't "making" money - they aren't making

anything. Value that was created by other people is being transferred to

them.

What makes "investing" so attractive is the very fact that it is a

means of acquiring money without working for it.

The following graph roughly shows the national income of America in

2000, classified by the US Treasury Department into the categories of

Labor, Capital, and Transfer income. The income being used here is

Family Economic Income (FEI).

According to the Treasury Department, Labor income includes pre-tax

wages, fringe benefits (employer provided healthcare, etc), and self

employment income. Capital income includes interest, pre-tax corporate

profits, non-stock capital gains, pension and IRA benefits, and earnings

on IRA and life insurance assets (note that profits from the sale of

stocks are not reflected in this data). Transfer income includes Social

Security, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Temporary Assistance for

Needy Families (TANF), Low Income Home Energy Assistance (LIHEA),

veteran's compensation, workers compensation, and food stamps. For a

further explanation see: http://www.ustreas.gov/ota/ota85.pdf page 18.

In truth, this entire pie represents Labor income. All of the value

created, which is measured as income in dollars, is created by work

being done. Transfer income is clearly value that has been taxed away

from Labor and then redistributed to others via the government. What is

called Capital income, however, is also value that is transferred from

the Laborers who create it to others via our financial institutions. It

is, effectively, also a tax on Labor.

It's more complicated than that however, because capital transfers

value not only from American workers, but from global workers as well,

and thus a portion of this Capital income represents value that is being

transferred to American holders of capital from foreign workers. This

graph also does not take all forms of capital gains into account, such

as the sale of stocks.

Capital income is disproportionably received by the wealthiest

segments of society.

This is not to say that there should be no return on capital, of

course there should or else there would be no point in investing in

capital. What capital investing is, ultimately, is a sharing of

resources. It is a means to pool resources so that resources that are

not being used by someone can be put to use by someone else.

Again, eliminating money from the picture helps to really understand

the role of "capital investing". (Note that capital investing is

different from say "investing in artwork", in which case there is no

sharing of resources or putting of anything to work.)

Let's say that a farmer works really hard and he purchases four

tractors over time for use on his farm, which he and his family use to

farm the land. After some years, his children leave and the farmer is

content to farm less and so now he has two extra tractors that he

doesn't use.

He goes down to the town center one day and he sees that a young man

is telling a crowd that he wants to start a large new farm, but he

doesn't have enough "capital" to do it himself, however anyone who

contributes useful resources to him will get a portion of his harvest,

based on the value that they contribute.

So, hearing this, the old man brings the young man two of his

tractors and gives them to him. This is "investing". He is giving his

capital to someone else to make use of with only the promise that he

will get a share of the harvest in return.

So, several people give capital to the young farmer, tractors,

horses, tools, seed, trucks, etc., and the young farmer is then tasked

with putting all of these resources to work. The young farmer promises

that he will give everyone vegetables every year equal to 4% of the

value of what they initially gave him.

In this way, the return on "investing" encourages individuals to pool

unused "capital" and allow other people to put it to work for them. The

young farmer then hires several farm hands and puts them to work using

the capital that he has been given by his "investors".

The food that he agrees to pay his investors in "dividends" has to be

taken out of the harvest that is collected through the work of the

laborers, and it will continue to be "paid" to the investors year after

year, indefinitely.

This is not to say that investing doesn't play an important role in

economic development, it does, as has been shown, but the fact is that

investing does not create wealth. The only thing that creates wealth is

work. Investing facilitates the ability to create new wealth.

All income that is generated, not only from investments such as this,

but from any kind of financial markets, is a transfer of wealth from

workers to property holders.

Since the 1980s the "return on capital" has increased steadily. The

share of National Income received by Labor in America has gone from

73.2% in 1979 to 70.5% in 2000, a 2.7% decrease. Furthermore, the growth

of government and non-profit income rose from 18.3% of National Income

in 1979 to 19.7% of National Income in 1995. This accounts for a 1.4%

increase in labor income by itself, meaning that if the expansion of

government and non-profit income is factored out, the increase in the

share of income going to Capital is even larger (however I don't have

the exact figures for government/non-profit figures for 2000 in order to

make a direct comparison).

Looking only at the corporate sector we see that Labor's share of

income fell from 83.9% of income in 1979 to 81.0% of corporate sector

income in 1996.

See: Capital's gain

So what we can see is that, not only is ultimately all value a

product of work being done, but that since the 1980s in America, the

share of National Income that goes to workers has been decreasing, while

the share of National Income going to Capital has been increasing.

During this same time, the "quality" of workers has actually

increased dramatically as well, with more workers having higher levels

of education, more technical certifications, and the cost of education

going up, which should, in theory (assuming a fair system), actually

increase Labor's share of income.

In 1979 only 67.7% of people over 25 had a high school diploma. By

2003 that number had risen to 84.6%. Likewise, in 1979 only 16.4% of

those over 25 had a college education and by 2003 that number had risen

to 27.2%. This "should" result in an increase in the share of National

Income going to Labor as workers "should" be more highly skilled. These

statistics don't even cover technical training programs, which have also

become increasingly popular. Not only are more people getting higher

levels of education, which means spending a larger portion of their time

in school training for work, but the cost of school is also increasing.

This means that Laborers are investing more in themselves than ever

before in America, and overall, getting lower returns.

See: Educational Attainment - US Census Bureau

All of this redistribution of value has been facilitated by the fact

that money is a representative of value that is now completely detached

from the value which is represents.

Summary

All wealth is created by work being done. Money is a means to

represent that value in order to make economic transactions more

convenient, but at the same time, by creating a representative of value

that is separate from the "object" abuses and distortions of the

economic system are also made "more convenient".

The only truly legitimate way to create value is to work to create

it, however, a major aspect of all modern capitalist systems has been

the development of legal ways to obtain value without working for it by

obtaining money. In our modern system money is the title that grants its

holder a right to value, even if the holder of the money didn't create

the underlying value. This has led, not only to widespread corruption

and economic confusion, but indeed it has led to a major effort to now

justify "incomes" of individuals that have no apparent relationship to

value creation. Indeed the belief in money and in our economic system

has become so great that the acquisition of money is now presumed by

many to be a justification in and of itself. In other words, instead of

value defining money, money now defines value.

If someone can acquire money then that in and of itself is

seen as a justification of the value of that person's actions in

acquiring the money. In fact, however, this is not so. Acquiring

money is not the same thing as creating value!

In addition to this, acquiring money is never done without a cost.

The sum total of all money in existence represents the sum total of all

of the actual real value that exists. The pie that is our

collective wealth is created wholly by workers. All money represents a

piece of that pie. When anyone acquires money for which they did not

work to create the value that it represents, this is not merely just a

"good fortune" for them, this also represents a loss of fortune for the

workers who created that value and did not receive title to it.

When, for example, currency traders "make money" via the buying and

selling of currency, resulting in a profit, they are transferring to

themselves rights to ownership of value that they have not created. The

trading of currency does not create value. There is no product. It's a

means of manipulating the system to extract value out of it - to

transfer it away from its creators.

Even when there is an "appreciation" of value in some object, for

example a collectable item like a painting, this also represents a

transfer of value from some other product of labor. Some have said

that it is not true that labor creates value because things can

"increase in value" over time, such as antiques.

This seems true at first, but on deeper inspection you see that

indeed what is really happening is that value is being transferred to

these items, and that without the actual creation of new goods and

services through labor these escalations of value cannot take

place. Labor is still actually creating the value.

All value is relative to other goods and services. Value is a social

relation that is a product of labor. For example, if an "economy"

contains one painting, a book, a bicycle, and a hammer, then the

relative values of these things may change among themselves, but they

can never exceed the sum total of all of them together.

The hammer may be valuable to someone at some time. It may be worth

both the book and painting together in a certain exchange. If the only

things that exist, however, are the items that have been mentioned, then

none of them can ever be worth more than all the other items combined.

Maybe later the hammer is not as valuable, and is deemed to only be

worth the book, and over time, maybe the painting is deemed to be worth

all of the other items combined. In that case, the painting would be

worth a book, a bicycle, and a hammer, altogether, in trade.

The only way that the painting can become "worth more", however, is

if more things are created. And thus we see that things

do not create value in themselves, and even the appreciation of the

market value of objects is a social process that is only made possible

by the labor of workers who create new value.

What money, finance, and modern capitalist ideology have done, is

they have turned economics into a shell game.

This is why we see so much discussion of wages and imports and

exports and taxes and this and that and the other. The conversation goes

something like this:

"If we raise wages then the cost of goods will go up."

"If we import goods from China then we can get them cheaper."

"If we import more cheap goods from China then our wages will go down

and we will lose jobs."

"You should invest your income from wages into the stock market."

"Stocks tend to go up based on corporate profits."

"Corporations increase profits by keeping wages low."

Sadly, this type of economic discussion has become prominent in

America today. This is nothing more than shell game economics.

This is the result of economic thinking based on money and finance.

It's an attempt to try and figure out a way to get something for

nothing. It's a belief that the system creates value.

The system does not create value. Money does not make money. Work

creates wealth, period.

Not only does work create wealth, but as John Locke made clear some

300 years ago, labor is the only basis by which we can truly determine

rights to property. As John Locke also pointed out, money is a means by

which the products of labor are transferred into another man's pocket.

Indeed, today the power of money has usurped the rights of labor.

[M]oney is a barren Thing, and produces nothing, but by

Compact, transfers that Profit, that was the Reward of one Man's

Labour, into another Man's Pocket.

- John Locke

Understanding Capitalism Part I- Capital and Society

Understanding Capitalism Part III- Wages and Labor Markets

Understanding Capitalism Part IV- Capitalism and Culture

|